| title | slug | tags | date | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Secretary Problem |

secretary-problem |

|

2021-11-30T08:16 |

The "secretary problem"1 (aka marriage problem or dowry problem), with its mysterious origin, first came in public on February 1960 issue of Scientific American in Martin Gardner's beloved column on recreational mathematics. The problem: "Imagine you're interviewing a set of applicants for a position as a secretary, and your goal is to maximize the chance of hiring the single best applicant in the pool. While you have no idea how to assign scores to individual applicants, you can easily judge which one you prefer. (A mathematician might say you have access only to ordinal numbers--the relative ranks of the applicants compared to each other--but not to the cardinal numbers, their ratings on some kind of general scale.) You interview the applicants in random order, one at a time. You can decide to offer the job to an applicant at any point and they are guaranteed to accept, terminating the search. But if you pass over an applicant, deciding not to hire them, they are gone forever."2

Secretary Problem at a glance:

- There is one secretarial position available

- The number

$n$ of applicants is known. - The applicants are interviewed sequentially in random order, each order being equally likely.

- It is assumed that you can rank all the applicants from best to worst without ties. The decision to accept or reject an applicant must be based only on the relative ranks of those applicants interviewed so far.

- An applicant once rejected cannot be recalled.

- You are very particular and will be satisfied with nothing but the very best.

(That is, your payoff is 1 if you choose the best of the

$n$ applicants and 0 otherwise.)

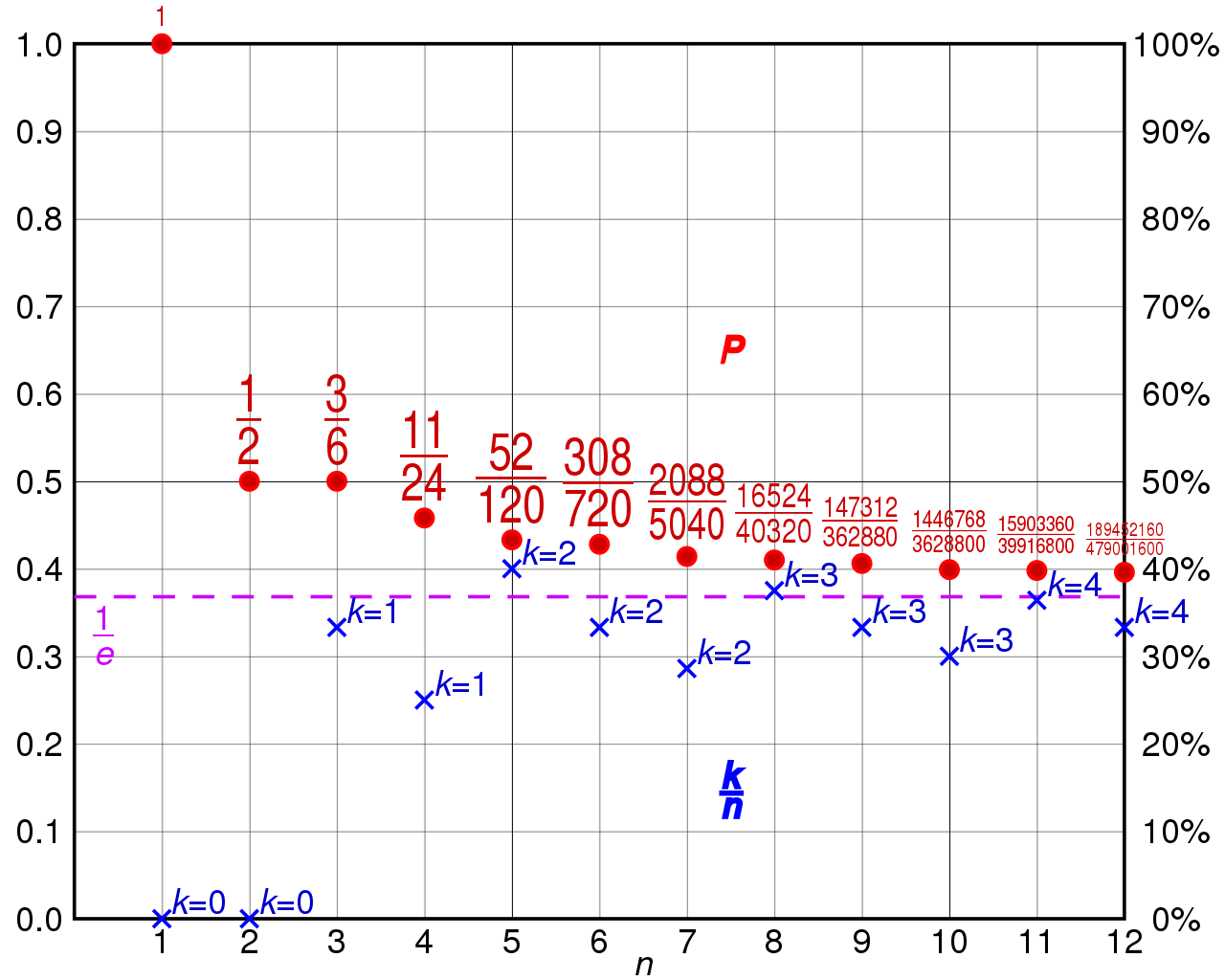

First, we can interpret the pass-and-reject rule where

The sum does not include when the number of automatically rejected applicants is

Integrating the sum letting

The value of

Thus, the optimal cutoff tends to

With this [[178bd100|algorithm]], there is a 37% chance of optimally finding the best one in any given amount of applicant pool virtually consistent. However, there is, in fact, a 67% chance of failure and thus very tempting to steer away from the solution. But, put things into perspective, brute force solution isn't remotely any better than the [[5e0d94ac]]#. For instance, reviewing a hundred applicants by random with no optimization algorithm would only result to only 1% success rate, that is when the best applicant is the last one in the pool, and with a million applicants, only a whopping 0.0001% chance of finding the best one, considering the interviewer have infinite amount of time to review all applicants. Using the optimal solution, the chances of finding the best applicant approaches 37% as the applicant pool grows, or put simply, the more applicants to review the more consistent the result is going to be.

Obviously, the secretary problem is impractical and does not apply to real life situations as there are too many variants. For one, applicant recall is always an option regardless if the interviewer further the search, provided the applicant is still available. Also, there is about 50/50 chance of being rejected by the applicants themselves which further complicates the optimal stopping. Furthermore, the interviewer knows nothing about the applicants other than the relative comparison to each other, but by how much? There is also a risk of passing up an exceptional applicants while in the calibration phase or before the optimal cutoff, and not to mention, a better one after hiring. Finally, a question of preparation over capabilities, as one could be so prepared than the ones who are more capable. There are a lot more variants the secretary problem oversimplified, but the fact we quantify this much is a good basis for other variations to come as did some brilliant mathematicians have, such as the odds algorithm3 or the [[5b12ca91]]#, after the seminal 37% rule.

<div class="tldr rounded shadow-2xl">

<h2>TL;DR</h2>

<p>

<b>Problem:</b> "Imagine you're interviewing a set of applicants for

a position as a secretary, and your goal is to maximize the chance of hiring

the single best applicant in the pool. While you have no idea how to assign

scores to individual applicants, you can easily judge which one you prefer.

(A mathematician might say you have access only to ordinal numbers--the

relative ranks of the applicants compared to each other--but not to the

cardinal numbers, their ratings on some kind of general scale.) You

interview the applicants in random order, one at a time. You can decide to

offer the job to an applicant at any point and they are guaranteed to

accept, terminating the search. But if you pass over an applicant, deciding

not to hire them, they are gone forever."

</p>

<p>

<b>Answer:</b> As the 37% rule suggest, reject the first 37% of the total

amount of applicants, assuming the applicants are reviewed randomly, to find

the relative ranking among them, then hire the first best applicant after.

</p>

</div>

- https://www.randomservices.org/random/urn/Secretary.html "The Secretary Problem"

- https://www.math.upenn.edu/~ted/210F10/References/Secretary.pdf "Who Solved the Secretary Problem?"

Footnotes

-

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Secretary_problem "Secretary Problem" ↩

-

Algorithms to Live By by Brian Christian and Tom Griffiths - Optimal Stopping ↩

-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Odds_algorithm "Odds Algorithm" ↩